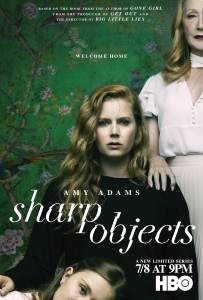

Reader, as I promised last month, we are talking about another book-to-T.V.-show adaptation, but this time, we’re talking about one that absolutely sticks the landing, which is the HBO adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects. Now, although this show may not have explained its mysteries quite as clearly as the book did, it did do a wonderful job in keeping to and visualizing Flynn’s unique feminist vision, which is what we’re talking about today.

If you’ve read the book or seen the show, you might be confused by what I mean by Flynn’s “unique feminist vision”, but bear with me; I’m going to explain myself. But first, a spoiler warning is in order here. This is especially important for Sharp Objects, as it is a mystery and I’m going to be spoiling the twists like there’s no tomorrow, so if you don’t want to know the end before you read/watch it, this your warning. Spoilers are now incoming in 3, 2, 1…

If you’re still here, you know the resolution to this show, and you may be wondering how having both of the villains in the series be women is in anyway feminist. Well, allow me to elaborate. The answer has less to do with the actual content of the show, and more to do with the subtext beneath it. What it boils down to is the way that Gillian Flynn weaponizes stereotypes. What I mean by this is her characters take stereotypes about the way women are and how they’re supposed to behave, and deliberately turn them into weapons. They become masks to hide their true intentions, another part of their arsenol that they deploy to get their way and to gain power, and in so doing, they reveal these stereotypes for the limiting and foolish things that they are (I mean, Flynn basically spells this out in the “cool-girl” monologue in Gone Girl, so it’s not like this is limited to just Sharp Objects). In Sharp Objects in particular, this plays out in our two villains, Adora and Amma Crellin. So let’s talk about how this works more specifically.

Let’s start with Adora Crellin, the mother of the show’s main character, Camille. Adora is a quintessetional Southern belle, or at least, that’s how she appears. She lives in the biggest house in town, is gracious and welcoming and mothering to all, and because of her status, pretty much runs the entire town without seeming to lift a finger or raise her voice, commanding respect with an excess of sugar. Kind of. This veneer of traditional feminine virtue is basically just a way for Adora to maintain her control, over the town and over her children. She basically owns the sheriff, mostly because in her polite, constantly offering ice tea, apparently weak way, she reminds him that she commands the power to make his life a living hell if he disobeys her in any way, mainly because of her wealth, but also because she has accumulated a lot of debts through her apparent generosity. She translates her benefactress identity into a game of tit for tat, making it hard for people to cross her without being reminded of all the “kindness” she’s offered them in the past. In this way, she uses those traits that are extolled as being the ideal virtues of femininity: kindness, nurturing, politeness, and turns them into weapons, using them as a means to make others beholden to her and cement her place at the top of the totem pole.

And as she does to the town, so to does she do to her own daughters. Adora has Munchausen Syndrome By Proxy, which essentially means that she causes injury and illness in her daughters, often by poisoning them (the stereotypical woman’s weapon), so that she can take care of them. She has already killed one daughter this way when the show begins, and she gets very close to killing the other two. So, once again, Adora takes the stereotypical function of womanhood, being a mother, and uses it as a weapon. Her desire to fulfill the stereotypical caring role of mother to the extreme leads her to murder and to incredibly endanger her remaining children. These stereotypes do not lead her to fulfillment of her true identity; they instead make her a petty tyrant, incredibly dangerous, and, you know, a murderer.

Which brings us to her daughter, Amma, because the same can be said of her, although she has different stereotypes at her disposal. Amma uses her mother’s desire to baby her to her own advantage, fully embracing her image as a young, innocent, naive and helpless girl, dressing in babydoll dresses, playing with dollhouses, and throwing fake temper-tantrums to keep the ruse going. But just like Adora, this childlike persona is a weapon that allows Amma to do whatever she wants to do. By tricking her mother into thinking she’s the perfect innocent daughter she can baby and fuss over, Amma has the freedom to do whatever she wants when she leaves her mother’s house, transforming into a wild child, who follows no rules, terrorizes other townsfolk, and dispassionately murders any other girl she feels might surplant her in her mother’s affections. Basically, by pretending to appear as “just a little girl”, another southern belle in the making, Amma is able to hide the fact that she is a sociopath, murdering over the tiniest perceived slights, and using the teeth of her victims to make the floor of her dollhouse, a profoundly ironic image.

So both Amma and Adora are using their feminine stereotypes as weapons, using them to hide their murderous ways. And by using stereotypes this way, Flynn uses them to directly call out how limiting and foolish those stereotypes are. They create a situation where these two women can get away with anything, because no one will believe they are anything but what they present themselves to be. A lack of belief in the complexity of these women gets people killed, which is a deliberate point that Flynn has made, not just in Sharp Objects, but in Gone Girl and Dark Places too.

And just to hammer home the point about complexity, we still need to reckon with our story’s lead, Camille, a character who can be quite unlikeable at times, but nevertheless, is sympathetic. And part of what makes Camille so prickly is the fact that she can’t be narrowed down to just one thing. She has aspects of multiple roles that might make her a stereotype, if the aspects of another role didn’t then directly contradict that previous stereotype. She is both a caring and loving sister, but casually cruel to the men in her life. She drinks and cuts herself, she sleeps around, but she refuses to see herself as a victim and is outright angry at Richard’s attempts at pity. She is snippy and shut-down, but deeply empathetic to the victims of the murders, even if she can’t quite show it. She is, basically, unwilling to be anything other than herself, and although that garners her judgement from the town because of her lack of conformity, it also protects her from sliding into the stereotypical role Adora wants her to fill, and thus, saves her from being murdered in the same way as her sister, and it allows her to escape the town and start anew in Chicago.

So, Camille is sympathetic because of her complexity and Adora and Amma are unsympathetic because of their complexity. If I try to make one point over and over again in this series: a well-developed female character is a feminist character, and all three of these characters fit that bill. Likeability is not, and should not, be a precursor to calling a character feminist. What makes a character feminist is whether or not she is a complex human being, and Gillian Flynn knows this, which is why none of her characters fall into the likeability trap, but all are feminist. And in addition to that, she uses and weaponizes stereotypes of female behaviour to point out how absurd and dangerous these stereotypes are in the first place. All of these traits are in full display in both the book and show of Sharp Objects, and it is those things that make it such a unique feminist piece of art.

That’s all I’ve got for you today, you guys should let me know in the comments your thoughts on the feminism in Sharp Objects or just your thoughts on it in general, stay safe, wear a mask, get vaccinated, and I’ll see you on Wednesday.

Until the next time.

That was a scary and disturbing book, and I couldn’t put it down.

LikeLiked by 1 person